New research shows how comets could be the source of life on planets outside our solar system

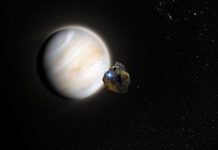

Scientists theorize that comets may have spread the organic ingredients necessary for the emergence of life on Earth. New research suggests that comets may also deliver these elements to exoplanets.

During the formation of the solar system, the Earth was bombarded by asteroids, comets and other space objects. How the planet obtained the water and molecules necessary for life is still controversial, but comets are considered the most likely sources of these substances.

But if comets could potentially bring the seeds of life to Earth, could they serve a similar function for exoplanets in other parts of the universe? To explore this question, a team of researchers from the Institute of Astronomy at the University of Cambridge developed mathematical models that helped reveal how comets could transfer similar vital elements to other planets in our galaxy.

While the study’s findings do not yet provide a definitive answer about the presence of life on other planets, they may help narrow the search for exoplanets that may support life.

“wandering” from planet to planet, spread life throughout the Universe?

“We continue to learn more about the atmospheres of exoplanets, so our goal was to find out whether there were planets where complex organic molecules could also be delivered by comets. It’s possible that the molecules that enabled life on Earth were brought in by comets, and the same may be true for planets in other galaxies,” said Richard Enslow, one of the study’s authors, who works at the Institute of Astronomy at the University of Cambridge.

Over the past decades, scientists have learned more about the prebiotic molecules found in comets. For example, NASA’s Stardust mission discovered samples of glycine, an amino acid and building block of proteins, in Comet Wild 2 (81P/Wild), and the European Space Agency’s Rosetta mission discovered organic molecules in the coma of Comet Churyumov-Gerasimenko (67P).

However, these organic molecules can be destroyed by strong comet impacts on the planet. So Enslow and his colleagues had to find scenarios in which a comet-planet collision occurs slowly enough to preserve the ingredients of life intact.

The study, based on simulations, found that the slowest impact velocities occur in solar systems where planets are densely packed. Comets moving through such systems are slowed down by the gravitational influence of the planets.

The simulations also showed that conditions for the emergence of life may be suitable on rocky planets orbiting red dwarfs. They are the most common type of star in the galaxy and are of interest to astronomers searching for exoplanets.

However, planets in such systems are subject to more frequent high-speed collisions with comets and the likelihood of life appearing there is low, especially if the planets are located at significant distances from each other.

“We can identify the types of systems that could be the subject of research to test different models for the origin of life. And this is another way to look at the amazing diversity of life on Earth and look for its analogues on other planets,” Anslow commented.