The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) is going “by the end of the decade” to build a base on the Moon for long-term residence and work of astronaut scientists.

Astronauts will be able to live and work on the Moon by 2030

This was reported by foreign media, citing a statement by Howard Hu, head of the Orion space program.

Howard Hu told reporters:

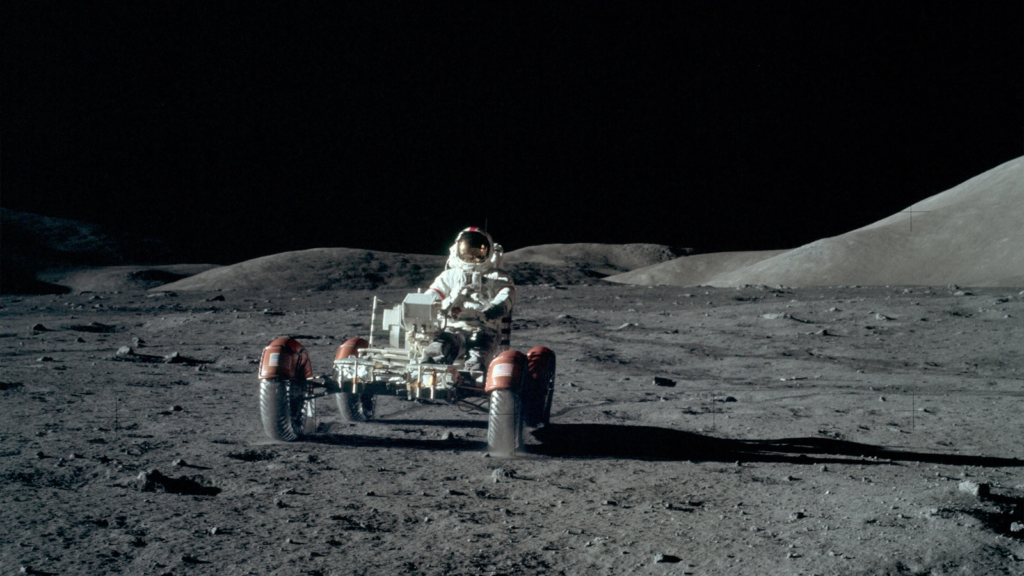

Of course, in this decade, our people will be able to live there for a long time, depending on the length of their stay on the surface. They will have dwellings, they will have rovers on the surface. We are going to send people to the moon, they will live and do science.

Recall that the giant rocket with the Orion spacecraft launched on November 16, 2022 from Cape Canaveral in Florida after a series of delays due to technical failures and hurricanes. Now the rocket is at a distance of about 19 thousand km from the moon.

Following the successful launch of the first Artemis mission, Nasa officials have spoken about their ambitions for the agency’s lunar programme, which could send astronauts to live on the Moon before the end of the decade.

Howard Hu, the Orion programme manager, said the Artemis launch was an “historic day for human space flight” and called it “the first step we’re taking to long-term deep space exploration”.

“Certainly, in this decade, we are going to have people living for durations, depending on how long we will be on the surface. They will have habitats, they will have rovers on the ground,” he told the BBC’s Sunday with Laura Kuenssberg programme.

“We are going to be sending people down to the surface and they are going to be living on that surface and doing science,” he added.

After several failed attempts, Nasa’s ‘Space Launch System’ (SLS) rocket launched from the agency’s Kennedy Space Centre in Florida last week, propelling the Orion spacecraft in the Moon’s direction.

The 98-metre SLS is the most powerful rocket Nasa has ever built. The megarocket’s 8.8 million pounds of thrust at launch is 13 per cent more than the Space Shuttle and 15 per cent greater than the Saturn V rocket used on the Apollo missions. In this crucial testing phase, it will fly further than any spacecraft built for humans: 40,000 miles past the far side of the Moon and 280,000 miles from Earth.

“We’re working towards a sustainable programme and this is the vehicle that will carry the people that will land us back on the Moon again,” Hu said.

The uncrewed mission is the first in the space agency’s Artemis programme, which aims to take humans back to the Moon and build the Lunar Gateway there – a space station where astronauts will be able to live and work.

Hu explained that the gateway would act as an orbiting platform which would be a staging post for lunar missions, with the astronauts taking “landers” from the platform to and from the Moon. Eventually, it could also be used to support further space exploration missions, such as journeys to Mars.

Sustaining human life for long periods of time on space missions is a significant challenge and one that requires resources such as water, building materials and fuel. As transporting these resources into space is expensive, a key enabler of future missions will be the ability to extract and use resources from the Moon, asteroids or Mars.

“Moving forward is really to Mars, that is a bigger stepping stone, a two-year journey, so it’s going to be really important to learn beyond our Earth orbit,” Hu added.

The UK has made contributions to the Lunar Gateway, working alongside the US, Europe, Canada and Japan. The nations have together developed the Artemis Accords, a set of principles to ensure a shared understanding of safe operations, use of space resources, minimising space debris and sharing scientific data.

The Artemis 1 mission is expected to last 25 days, including outbound transit, the journey around the moon and deployment of satellites, followed by a return transit before splashdown in the Pacific Ocean in December.